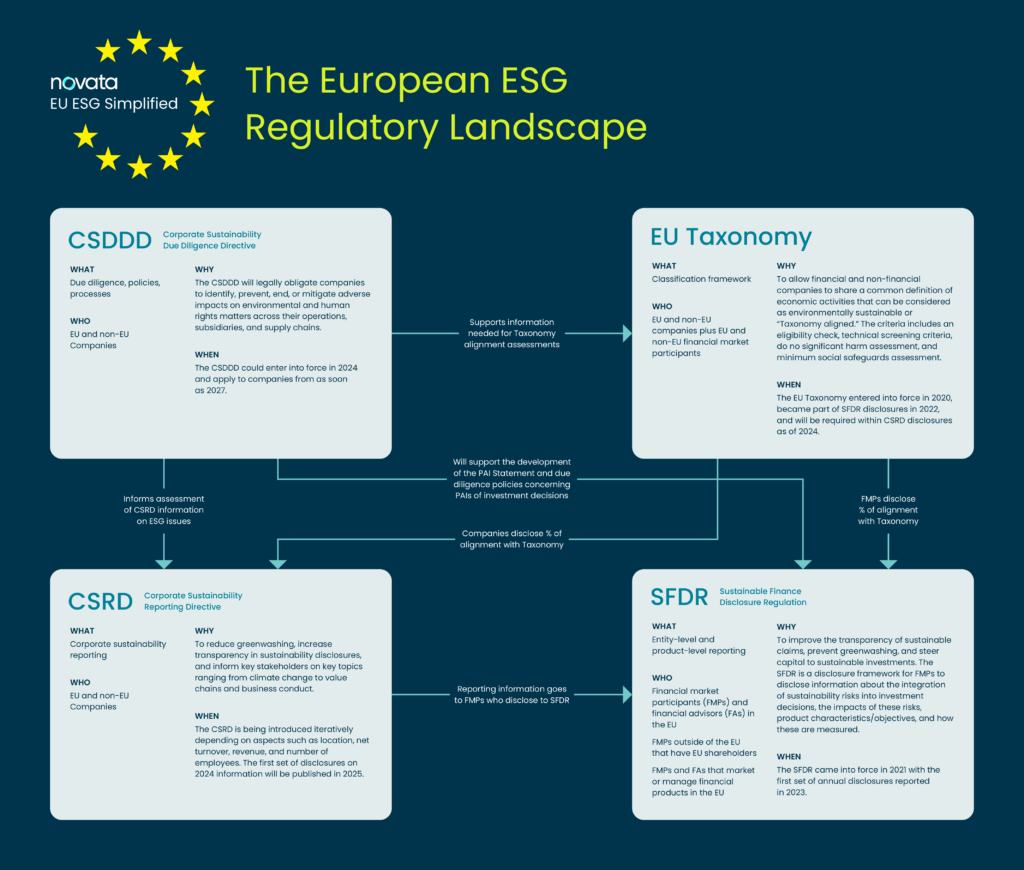

The European ESG regulatory landscape has been pivotal in setting up disclosure regimes for both investors and companies across the globe. Although many lessons have been learnt along the way such as those demonstrated through the latest SFDR consultation, it cannot be denied that Europe is setting up an ESG disclosure blueprint for countries and organizations across the world to either adopt or build upon to suit their jurisdictions.

When looking at the progress made to date, it is important to remember how these measures were developed. In 2018, the European Commission published its Action Plan on Sustainable Finance to set out a comprehensive strategy to build a bridge between finance and sustainability. This was complemented by the EU Green Deal, which aims to make Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, and the Strategy for Financing the Transition to a Sustainable Economy. Implementation of the Action Plan has come from several measures in the form of regulations, directives, delegated acts, and standards. Some of the most commonly recognized include the EU Taxonomy, the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), and the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Standards (CSRD). However, to date, there is a lack of understanding of how the regulations connect, with some being heavily reliant on the outcomes of others.

One reason why this connection is often missed comes from the timing of each regulation being adopted. Take the SFDR as an example. The SFDR came into effect before the CSRD, but it relies upon much of the information provided by companies reporting under the latter regulation. In turn, the CSRD is partially reliant upon the due diligence processes set out within the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD or CS3D), which is yet to enter into force. The EU Taxonomy was one of the first regulations to be implemented, followed by the SFDR, then CSRD and the CSDDD, which is likely to come into force in 2024. Due to its complexity and multitude of requirements, some argue that the CSRD should have come after the SFDR; however, others argue that the ordering should have focused on first implementing processes such as due diligence guidelines in the CSDDD and data collection habits required for the CSRD, before turning to disclosure regulations such as the SFDR.

Transparency is paramount, but without key processes, procedures, and data management systems, reporting has been almost impossible for some investors in scope with the SFDR. At Novata, we have developed a workflow to help explain how these four key European ESG regulations interact and influence the meaningfulness of each other.

Download the European ESG Regulatory Landscape infographic.

Breaking Down the EU ESG Regulatory Landscape

The EU Taxonomy

The EU Taxonomy is a classification system to establish environmentally sustainable activities. While this is useful for examining environmental criteria, the establishment of a Social Taxonomy is still pending (with no due date). This makes the assessment of sustainable investments (in the eyes of the EU) and their alignment to the Taxonomy somewhat incomplete. One sector that often struggles to demonstrate that it is a sustainable investment with sustainable outcomes is the healthcare sector, which is not currently an EU Taxonomy-eligible sector and would instead benefit from a Social Taxonomy. Despite its flaws, the EU Taxonomy has been integrated into product disclosures required within the SFDR and the CSRD, which will require all companies in scope of the CSRD to undertake an EU Taxonomy alignment assessment.

The CSDDD

The CSDDD or CS3D complements the Taxonomy Regulation as it aims to collect information about companies and their value chains to support EU Taxonomy alignment assessments. It aims to ensure companies are transparent about their assessment and management of sustainability risks and impacts concerning human rights and environmental impacts, including those across their value chain. It will require companies to undertake due diligence on their own activities and those of their suppliers. The framework will include steps to identify, end, prevent, mitigate, and account for negative human rights and environmental impacts within the company’s operations, value chains, and subsidiaries. This will be key in supporting companies to develop the relevant processes to collect information for the CSRD as well as support them in identifying adverse impacts as per the CSDDD due diligence duty.

The CSRD

The CSRD not only includes the need to identify, assess, and disclose material impacts, risks and opportunities, but it also requires companies to undertake assurance. It is in place to support corporate sustainability reporting, but any entity (including investors) that meets the CSRD thresholds must align, meaning that many EU companies, non-EU companies, and investors will need to make CSRD disclosures. The regulation will require a huge amount of data collection, which must be informed by the topics deemed to be material to a company following the completion of a double materiality assessment. The double materiality assessment will inform the sustainability due diligence processes needed for the CSDDD and vice versa. Importantly, much of the information disclosed as part of the CSRD will also provide information investors need to disclose in their SFDR disclosures.

The SFDR

The SFDR is complemented by all of the regulations above. Firstly, Article 8 and Article 9 products (e.g., funds) must disclose Taxonomy alignment. Firms or fund managers can use the Taxonomy framework to demonstrate their proportion of sustainable investments using the technical screening criteria (TSC), do no significant harm (DNSH) criteria, and minimum social safeguard criteria set out. Secondly, financial market participants (FMPs) with more than 500 employees must publish a statement about their due diligence policies concerning Principal Adverse Impacts (PAIs) and investment decisions — the collection of the information used to publish the statement will be supported by the CSDDD. Finally, although subject to materiality, much of the information disclosed from companies as part of the CSRD will feed into the information needed for SFDR disclosures as well.